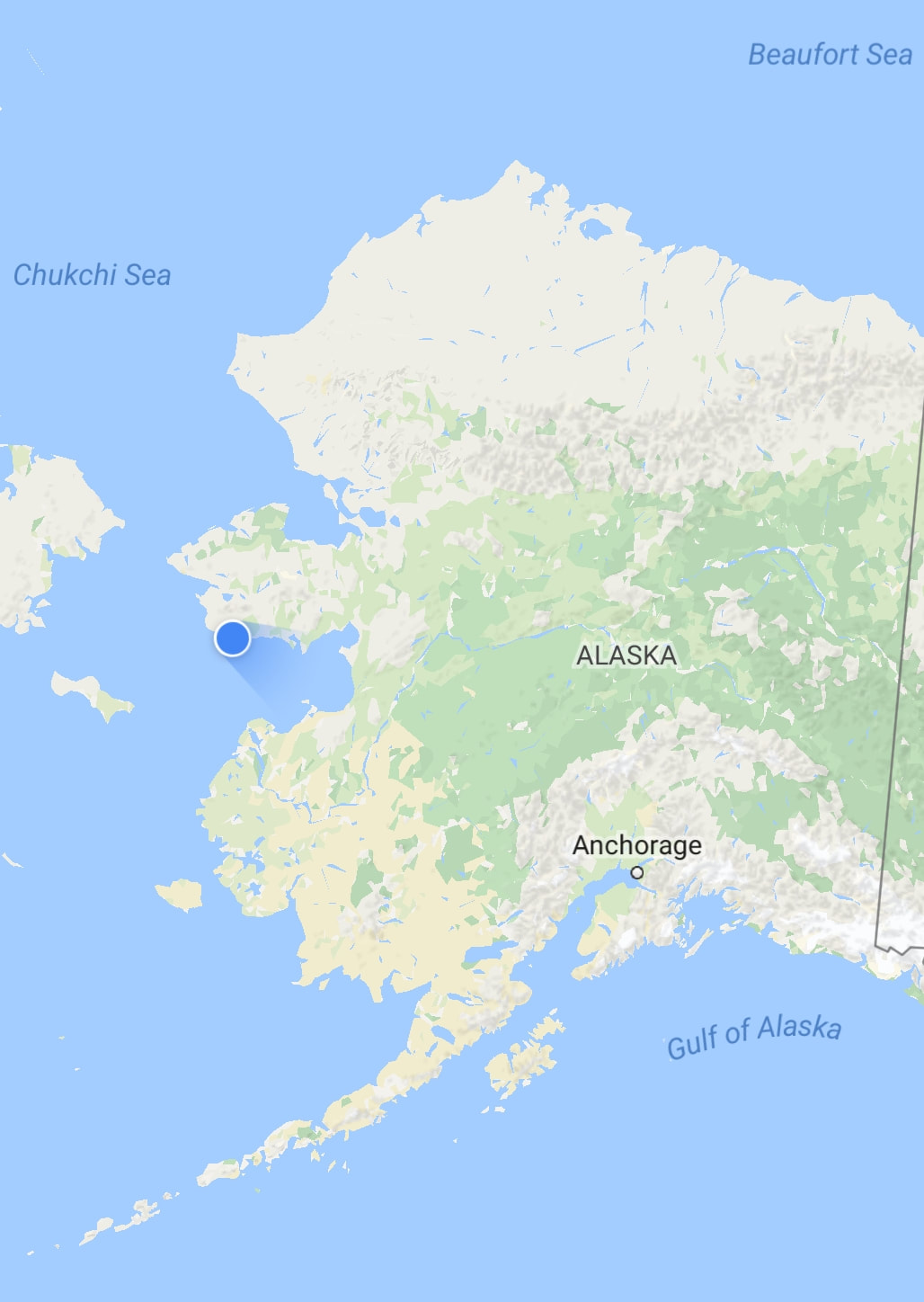

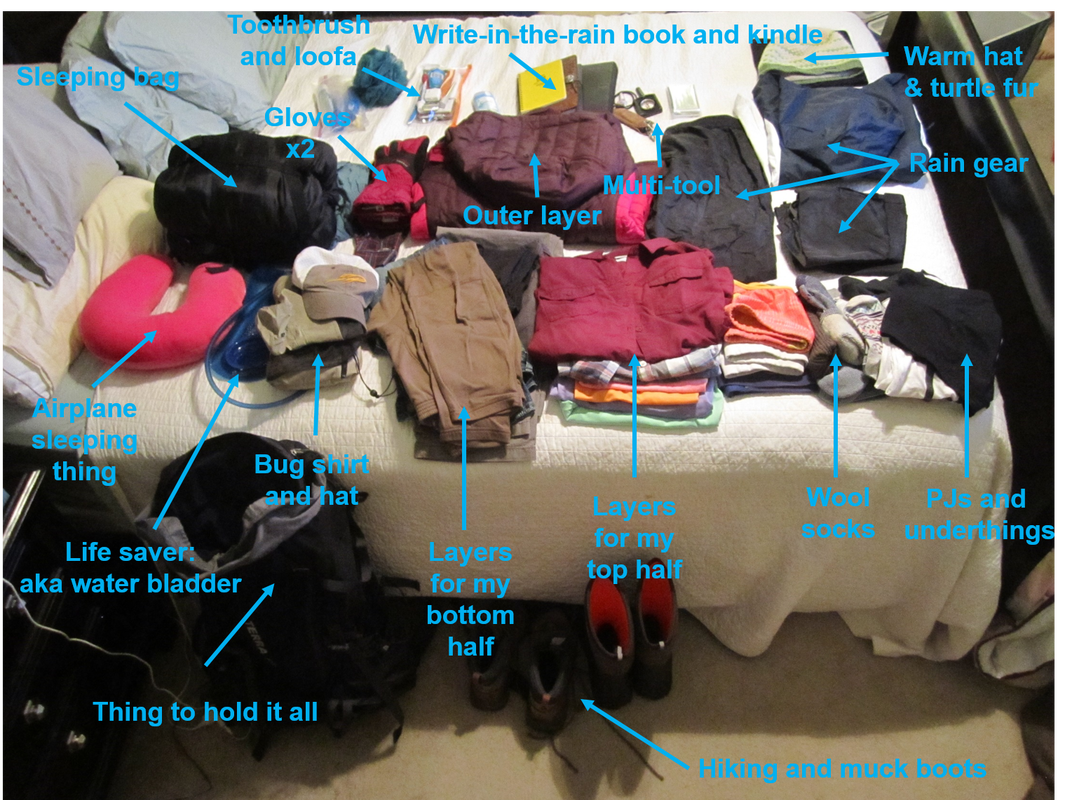

When it comes to a day-in-the-life as a graduate student chemist, the stereotypical imagery of someone sitting at the lab bench in a white lab coat and goggles, with a few beakers and maybe a Bunsen burner nearby isn’t too far off. Okay, maybe not always. But the part about being in lab all the time is pretty spot on. Even when our work involves environmental samples like soil, sea water, or plant material for example, someone else—a collaborator usually—will just ship us the samples for analysis. But as an interdisciplinary graduate student in the Bredesen Center working at Oak Ridge National Lab, the opportunity to engage in field work is not only possible, but encouraged! Which is why I am in Nome this week, in western Alaska on the Seward Peninsula, collecting what I hope will be the last set of samples needed to complete my graduate work. Yay! This is my fourth summer in Alaska and I think I’ve finally got the packing part down. All of this… …somehow makes it into that thing-to-hold-it-all in the bottom left. Also, did you know they make PAPER you can write on, IN THE RAIN?! Well, I didn’t. It’s the little things I guess. Throughout the week, I’ll be working at two field sites inland a bit on the Seward Peninsula as part of the DOE-led NGEE-Arctic (Next-Generation Ecosystem Experiments) project. NGEE’s overarching goal is to reduce uncertainty in climate models by improving our understanding of how Arctic systems will respond to climate change. How do we do that? Historically, computational modelers and scientists running the experiments have worked in separate silos. So, any data or observations collected in the field, first had to be published before the modelers could insert those numbers into their model to see how well their simulation matched to reality. The experimentalists would then have to wait for that simulation to be published to inform their next set of experiments. Zzzzz...come on already! What NGEE aims to do is bring everyone together on one project, working on the same science questions. Those who develop and test climate models, together with those collecting the data in the field and laboratory. That way, the observations and measurements taken in the field or the lab can be fed directly into the models, and each new and improved simulation can be used to help guide experiments right away. Throughout this interdisciplinary process, with each iteration, we learn more and more about how unique and vulnerable landscapes like the Arctic are being impacted by climate change, and our predictions of how they will respond in the future improve too. Where do I fit in? My graduate work falls under the biogeochemistry science questions. As a chemist, I’m interested in understanding how the compounds found in soil water can be used as chemical signature of biological activity, ultimately helping to detect hotspots of vulnerability across the landscape. In other words, where across the landscape is the carbon and nitrogen more likely to be released in the form of potent greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), or nitrous oxide (N2O)? By characterizing the chemistry of the soil water at the molecular scale, and correlating that with changes in the microbial community and other environmental factors, we can gain a deeper understanding of why some areas might be more likely to store or release carbon.

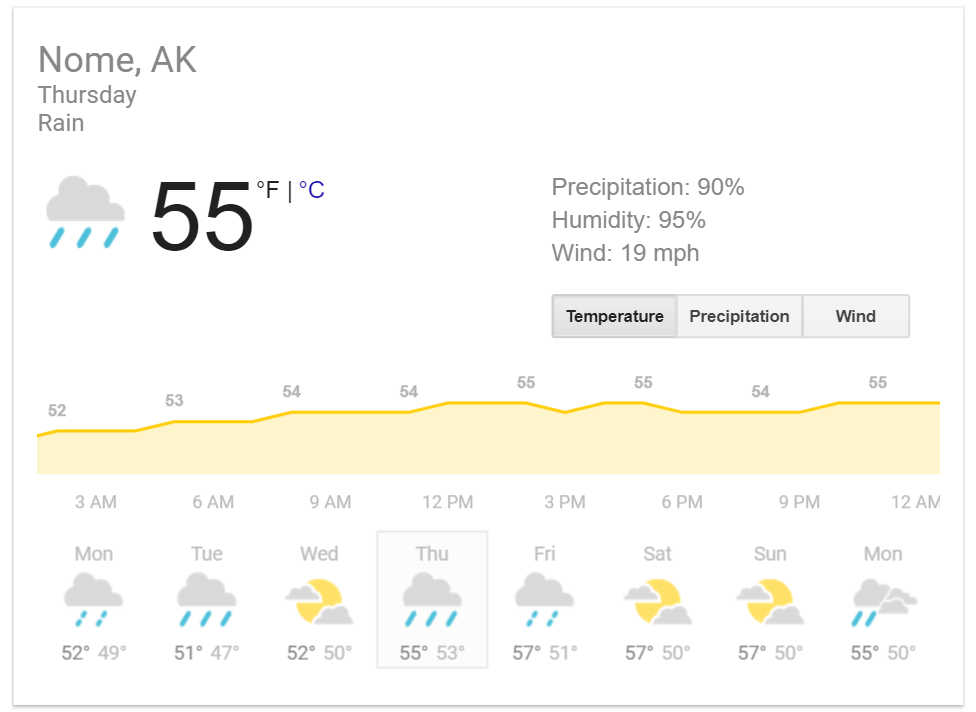

The “Three Lucky Swedes” first settled this town in 1898, reaching a population of about 10,000 after just one year. Once they started finding gold on the shores of the Bering Sea, thousands more started to pour in each year. But even before all that, Iñupiat communities settled this area and hunted game back to prehistoric times. They built and used wooden boats called umiaqs to go whaling each summer, and even now, many coastal communities in Alaska hold a festival each year to share the whales brought back by successful whaling crews. Now, just under 4,000 people reside in this sleepy mining town, but each year the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race still finishes on Front St., just a block away from where we’re staying this week! Nome is quite literally a one stoplight town, but it has its own character and charm, that’s for sure. This is only my second time here, but everyone I’ve met has been so friendly, and genuinely interested in what brings me to the place they call home. I guess they can tell I’m from out of town somehow… It took three flights over 24 hours to get here. It’s a 1-2 hour drive on pothole-studded, dirt roads to get to our sites each day. And once we’ve reached the site, we load up our packs with extra layers, rain gear, sampling tubes, data loggers, extra batteries, and bottles of water, and begin our hike across the tussock tundra—which can only somewhat be described as walking across thousands of bowling balls covered in wet laundry—to finally reach our plots where we start collecting data. The weather is unpredictable with freezing temps and biting winds possible even at the height of summer. And on one of the few warm, sunny days we do get, the swarms of mosquitoes remind us how inhospitable the Arctic can be.

And yet, I still wouldn’t trade any day in the field for a day back at the bench in my lab coat and goggles surrounded by beakers. Field work can be challenging. You never quite know how things will pan out, but at the end of it all, when we hit pay dirt and can share a new nugget of information with the scientific community, I’m reminded of why it’s all worth it. 😉

2 Comments

Susan Steiner

8/3/2017 11:25:35 am

Pay dirt and a new nugget of info....your writing skills are excellent. Thanks for shedding light on why NGEE!

Reply

Mallory

8/3/2017 11:30:35 am

Hey Sue! A few puns here and there never hurt anyone, right? :) Thanks for reading!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Hello!Welcome to Think Like a Postdoc. If you're a fan of science as much as I am, and/or are curious about getting a degree in a STEM field, or pursuing an interdisciplinary graduate degree (all from the perspective of a graduate student), then you're in the right place. Think Like a Postdoc also includes posts about my current lab and field research, including analytical chemistry, Arctic biogeochemistry, and energy & environmental policy. Comments and questions are always welcomed. And please tell me what you want to hear about next! Top PostsQuestions to Ask Before Choosing Grad Program

Dirt Popsicle First Semester of Grad School Field Work in Alaska Science Conference Dos and Don'ts Women in STEM Series Things I've Learned in Grad School Series Blogs I FollowMass Spectrometry Blog

Metabolon Compound Interest The Grad Student Way SouthernFriedScience Science Blogs Anthony's Science Blog The Thesis Whisperer GradHacker Fossils and Shit Science Communication Breakdown Science Communication Media Categories

All

Blog Archives

August 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed